At Republic’s Edge: Ladakh, Manipur, and Federalism

Every political reordering carries within it a promise of dignity, of empowerment, of a more intimate connection between the State and society. Ladakh in 2019 seemed, for a fleeting moment, to embody that promise. The separation from Jammu and Kashmir, its elevation to a Union Territory, and the newly visible embrace of New Delhi were interpreted as long-awaited recognition. For sections of the Buddhist leadership in Leh, it was liberation from a political architecture they imagined had rendered them peripheral.

Yet, like so many political promises in contemporary India, the euphoria proved transient. The celebratory rhetoric of empowerment has now given way to a pervasive unease that sits at the heart of Ladakh’s political life. Five years later, the region stands engulfed in a crisis of authority and voice. The absence of a legislature, the hollowing of autonomous institutions, and the growing distance between governance and the governed have shattered the initial optimism.

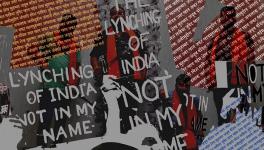

The protests in Leh and Kargil are not merely expressions of local discontent. They are a reminder that constitutional redesigns cannot indefinitely defer the question of representation. When thousands, Buddhists and Shia Muslims alike, demand statehood and Sixth Schedule protections, they are articulating a profound critique of an increasingly centralised republic. Their mobilisation is democratic in method and constitutional in aspiration; its moral force lies precisely in its repudiation of the sectarian vocabularies that have come to dominate national politics.

Global democracy indices, V-Dem and Freedom House among them, have gestured to India’s democratic backsliding. Ladakh offers a vivid demonstration of how these abstractions acquire material form. For the first time, the fault lines of India’s new centralised federalism are not visible in ideology alone but in the lived realities of people at the margins.

Development Without Democracy

In the official imagination, centralisation is often justified as efficiency. Ladakh exposes the deep limitations of this illusion. The region today confronts a paradox: never has it been more directly governed by the Centre, and yet never has the alienation from state authority felt more acute.

The promise of swift development has faltered against the realities of unemployment, shrinking opportunities, and a state apparatus increasingly staffed through deputations from outside the region. Local youth educated, skilled, hopeful find themselves displaced in their own homeland. The wounds inflicted by the collapse of tourism, the fragility of mountain ecologies, and the accelerating retreat of glaciers have been deepened by an administration structurally incapable of responding to local priorities.

The once-celebrated Autonomous Hill Development Councils now stand diminished, their fiscal and political authority reduced to tokenism. Governance has become a monologue delivered through bureaucratic channels rather than a negotiation with local aspirations. It is no surprise that Ladakh’s people seek the Sixth Schedule, not as a backward-looking assertion but as the only shield available against economic dispossession and environmental vulnerability.

This predicament resonates far beyond Ladakh. Manipur offers a still more tragic manifestation of the State’s incapacity to mediate conflict, rebuild trust, or uphold its most basic responsibilities. The humanitarian crisis unfolding there is not an aberration; it is symptomatic of the weakening of constitutional guardrails that once ensured that the State could command legitimacy even where it commanded power.

Across these regions, the story is uncannily similar: the erosion of institutional intermediaries between the State and the citizen, the marginalisation of representative bodies, the entrenchment of executive discretion, and the dangerous belief that authority can substitute for trust.

Margins as Mirrors of the Republic

The crises in Ladakh and Manipur are not isolated disruptions; they are mirrors held up to the republic. They force us to confront an uncomfortable truth: India’s federalism is being reimagined not as a compact of shared sovereignty but as an instrument of centralised control. This transformation carries profound risks for a plural society.

The unity of Ladakh’s Buddhists and Muslims in demanding constitutional safeguards is a quiet yet powerful indictment of the national narrative that polarisation is the natural order of Indian politics. Their movement demonstrates that when democratic institutions shrink, communities often rediscover solidarities that the state prefers to ignore.

In its cross-communal character, the Ladakh movement speaks a language more constitutional than the constitutional order it confronts.

What is at stake is not merely the administrative design of a remote region. It is the very idea of the republic: a republic that once prided itself on listening to its peripheries, on weaving dissent into deliberation, and on recognising that the legitimacy of power depends on the consent of those governed.

To neglect Ladakh’s pleas is to deepen a sense of betrayal among those who once cheered the post-2019 reconfiguration. To normalise the tragedy of Manipur is to concede that some citizens can be abandoned without moral consequence. And to continue on the path of centralisation is to risk hollowing out the federal spirit that has been central to India’s democratic endurance.

The margins are speaking, not in rebellion, but in democratic assertion. They ask for what any republic must provide: dignity, representation, and trust. Their warning is clear. A State that demands loyalty but withholds voice cannot indefinitely claim legitimacy. The challenge before the Centre, then, is not merely administrative; it is deeply moral.

Ladakh’s movement, peaceful and resolute, is a reminder that the republic thrives only when it has the humility to listen. In doing so, it holds up a mirror to a nation that must decide whether it still recognises the constitutional promise at the heart of its federal design.

Dr. Waseem Ahmad Bhat is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Akal University, Punjab. Dr. Javaid Ahmad Bhat is Assistant Professor at IUST, Kashmir. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.