Budget’s Service Sector-Led AI Strategy: Perils for Educated Workforce

Representational Image. File Image

The Economic Survey’s and Union Budget’s observations of the economic impact of AI is well-timed to respond to the large-scale crisis the IT sector has been confronting over the past year, but possibly unstrategic given its continued service sector focus, we argue. Our contention is that the latter will further aggravate the former, in addition to causing other forms of economic upheavals.

India: at the Periphery, a Labour Supplier

India confronts the AI revolution from the periphery, i.e, at best as a supplier of labour, and definitely not as owner of any kind of capital relevant to the AI revolution in the current scenario. Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia Corporation, conceptualises the AI ecosystem as a five-layer cake, with energy at the bottom, upon which chips, infrastructure, models and applications are stacked.

Currently, the two global powers, US, followed by China, lead on all fronts except energy, where China leads. Countries, such as Taiwan and South Korea are also key players in the AI value chain at the chip and infrastructure layer of Huang's cake.

In the 1980s, when these countries were building capacities, India also had nascent initiatives, which were not to attain fruition in the background of a failed dirigiste regime. Hence, India lags years behind these key players in terms of its electronics industrial ecosystem given its high import dependence and sub-par domestic capabilities which continues well into the post-liberalisation years of unstrategic FTAs (freetrade agreements) and World Trade Organisation-led neo-imperialism.

Limited Successes of Indian IT revolution

Second, India’s peculiar case of a partly successful software revolution sets it apart from its peers in the Global South. Even as a supposed software success story, India’s primary item of software export in the balance sheet has been services for the longest period, calling into question the nature of this success. The advancements made by the industry in transitioning to high-value front-end services have been limited, and in the area of product development there has been only pockets of success mostly restricted to some sectors. It is safe to say that in the nearly two-and-a-half decades of our software journey, evolutions have been modest. The sector has existed as an “enclave economy” with no backward or forward linkages.

That said, despite the limited success achieved in the global value chain context, the IT service sector did play two crucial roles in the country. First, that of bridging the significant gap in the current account by bringing net positive cash flow, and, second, in our opinion, more importantly, by absorbing a major chunk of the high-educated work force graduating with technical degrees in the country.

Even the much-celebrated 100% placement of the Institutes of Eminence (even for the technical branches of engineering) has been thanks to the IT service sector acting as the employer of last resort. It is this capability of the sector that now seems to be under threat in the AI revolution.

Will AI Displace Labour?

As in every previous ‘revolution’, the question obviously is, “Will the technology displace labour?”, and as before, the answers are divided into two messy camps. The most unfathomable, yet debatably “successful” replacements have occurred in the creative industry, triggering instances of mass firings (and important political questions) across sectors in establishments of small and large sizes that have been met with various kinds of success, depending what one might call success. The attempt here, however, is not to make the obvious Luddite argument of labour displacement; but to examine its sectoral and skill-specific connotations in the Indian context.

Our current analysis was motivated by a recent study published by Open AI, where they measured the capability of Frontier AI models in completing economically valuable tasks by pitting them against human experts.

The Open AI study reported:

“.... frontier model performance on GDPval is improving

roughly linearly over time, and that the current best frontier models are approaching industry experts in deliverable quality. We analyze the potential for frontier

models, when paired with human oversight, to perform GDPval tasks cheaper and

faster than unaided experts.”

Surely, given the fact that the study was conducted and funded by the corporate that operates ChatGPT, the conflict of interest in operation is not to be neglected, despite its rigorous methodology.

In our analysis, we mapped various professions the Open AI study predicted would be easily replaced by AI models into the Indian context using NCO (National Classification of Occupation) 2015 codes. This exercise revealed that these constituted the vast majority of jobs that our high-educated technical graduates vie for come placement season, including but not limited to ‘Software and Application Developers and Analysts’, ‘Business Service Agents’, ‘Finance Professionals’, ‘Legal Professionals’, ‘ICT Services Managers’, to name a few.

This is a worrisome reality for a country brimming with young graduates and readying itself to reap the advantages of a demographic dividend. Employers have already caught the winds and have started gearing up for this future, as is evidenced by the recent spate of AI-induced layoffs, recruitment-freeze, and other forms of labour-restructuring. In all previous technology revolutions, a given job was fragmented into its constituent tasks, and some parts of it automated, the same has happened in the AI revolution also. For India, and for the sectors it impacts, it spells deep trouble.

The Educated Workforce at Risk

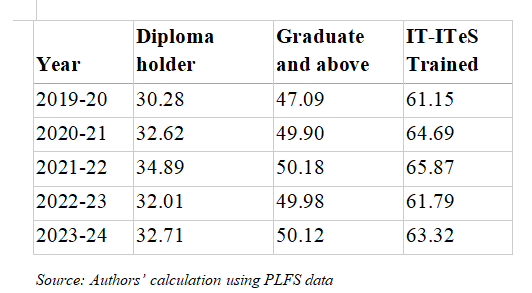

Table 1: Percent Share of different groups in AI exposed jobs

As per the calculations we performed on PLFS (periodic labour force survey) unit level data 2019-20 through 2023-24, it has emerged that a vast majority (~46% in 2019-20 and ~50% in all other years) of the country’s graduates and above are employed in sectors that are now prone to AI-induced labour displacement. Making things worse, IT/ITeS trained workers also figure in a higher proportion (~61% in 2019-20 and ~66% in 2021-22) in AI-prone jobs than in the rest of the employed labour force. Even among our diploma holders, a significant percent (~30% in 2019-20) and ~35% in 2021-22 are vulnerable to AI-induced displacement (See Table 1). In an economy reeling under the pressure of an employment crisis of epic proportions, this situation arguably poses further threat.

The AI revolution poses a hitherto unseen problem: contrary to popular perception (read CEO prescriptions), we might not be able to “upskill our way out of this latest technological revolution”. Those prone to threat of displacement are already the most upskilled of the lot. Unlike the erstwhile revolutions where physical abilities were replaced by technology, this time around, cognitive abilities have been attempted to be replaced, more or less successfully, it needs to be said. What this means for new graduates, is that it severely truncates a ready-made career trajectory that had for the past few decades seemed like an achievable aspirational goal.

As the technology begins to be deployed across the sector, there could be a drastic reduction in human involvement in many tasks, further weakening the bargaining power of labour in the sector, and a possible shift of power from labour to capital as a second, but crucial consequence.

In this phase of the AI revolution, India is set to suffer so badly, primarily because of its partially successful software revolution, with its singular focus on IT services exports, and no backward or forward linkages as discussed in the outset, which the government now seems to be intent to enhance.

That said, as economies progress in the AI revolution, our policies need to have a steady grasp on what automation means under AI. Tasks which were once considered ‘non-routine’, and therefore, not amenable to automation, have now been automated, demanding a radical shift in our theoretical understanding of what now constitutes a ‘safe job’. The above analysis is solely based on the current phase of the revolution and its several aspects are subject to change come the next phase, nevertheless, we believe, there is merit in this examination; to pave way for a policy path that right historical wrongs.

Anjana Kesav is a PhD scholar at Centre for Development Studies, Trivandrum, and is interested in questions of labour and the informalisation of the formal. Sachin Varghese Titty is a PhD scholar at Centre for Development Studies, Trivandrum. His research examines Industrial Policy and the economics of Knowledge Production. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.