Return of the Long Working Day!

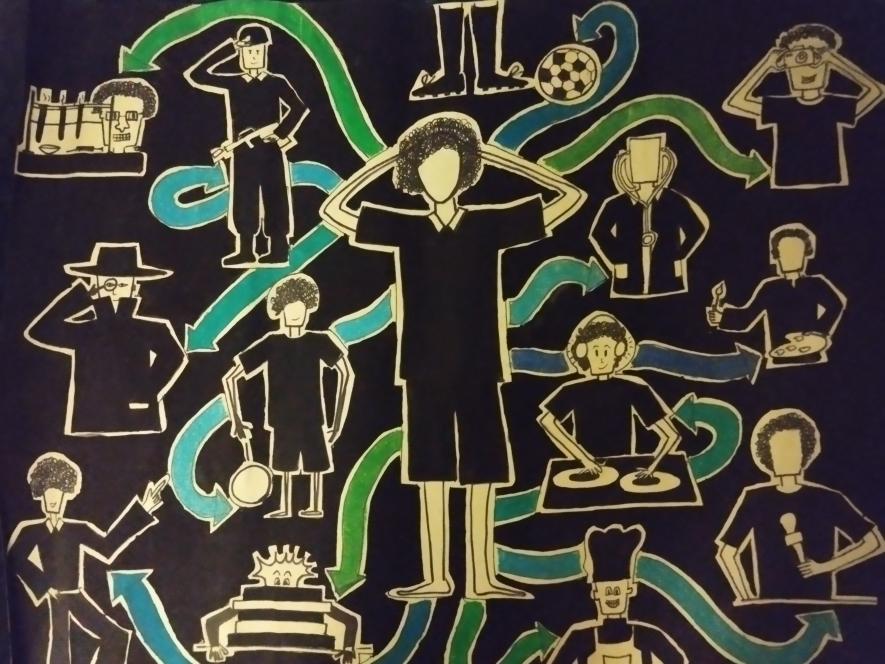

Illustration by Trina Shankar.

The Maharashtra government, following in the footsteps of Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Uttar Pradesh and Tripura, has resolved to address their widely prevalent issue of over-working by legalising it. The state cabinet has given the go-ahead for extending working hours from the current 9 hours to 10 for the private sector by amending the Factories Act, 1948 and the Maharashtra Shops and Establishments (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 2017.

Good old Karl Marx red-flagged (pun intended) this text-book practice of exploitation centuries ago. The lengthening of the working day was the easiest way to squeeze out surplus value.

I have lived in Mumbai for a short duration as part of its workforce, but long enough to recognise its toxic relationship with time; the city, in fact, never sleeps.

I had quit engineering because I foolishly believed I could escape the corporate world that had seemingly enslaved my friends by moving to the social sciences, only to wake up to the bitter reality that the job market here was corporatised, perhaps even more, that it posed a contradiction.

My job was at a start-up providing ESG consultancy solutions to Fortune 1000 companies in India and abroad so that their annual reports could look greener. ESG was supposedly the next big thing, consultancy firms were now in the business of solving the climate crisis, one sustainability report at a time. I told myself this was the most socially conscious job I could land that would help me meet the high living expenses of Mumbai.

My flat in Chembur, which I rented with my friend and colleague, ate up a huge part of my earnings, yet left me just enough to live the life of a “corporate girlie” in Mumbai. We bought fancy food, occasionally dined at high-end restaurants, and bought expensive clothes.

Corporate slavery was more expensive in India’s finance capital than it was in the country’s Silicon Valley. There was no other way to feel gratified at this job. We occasionally discussed the politics of it all to make the only possible use of our Development Studies degree.

When friends claimed that my corporate life contradicted my past political affiliations, I bought The Capital off of my first salary to prove them wrong. But our working hours were flexible (for the company), leaving me no time or mental space to read anything apart from what was required at the job.

I realised my career choice did not contradict my politics, it merely helped me theorise it better. Our flexible working hours, a part of which was spent at the office three days per week, were classified into billable (chargeable to the client) and non-billable (paid for through the salary), always extended well-beyond the legally mandated nine hours per day in Maharashtra. This, added to the close to three hours (going up to five on busier days) spent on the short 17 km commute during which laptops were to remain on, meant that idle time was minimal.

Our initial plan of only eating “healthy home-cooked meals” had to be compromised within a month as we shifted to a tiffin service to have some free time, apart from sleep.

Every employee is assigned a performance manager who is to ensure that the minimum eight hours is met, and all of it are billable. The project manager, tasked with a contradicting responsibility is expected to ensure the employees under them finish assigned tasks well-below the agreed-upon time. As a result, there exists a tussle of sorts between the two managers, one wanting to maximise your billable hours and the other struggling to minimise it.

Everyone was time-stressed. Four out of the six of us who joined the organisation from our campus, resigned within a year due to various forms of work-stress-related medical contingencies. Even though HR-instituted and legally-mandated norms on workplace harassment exist, these time-related targets are held and adhered to religiously by fair means or foul.

During my first 1.5 months at the company, in the absence of new projects being sanctioned, most of my hours were to be categorised as unbillable. I was proving to be a liability.

My first-ever project that came in my second month had too few billable hours to justify the actual hours I spent at work. I was assigned 15 billable hours of job out of the 120 hours I actually had. There was nothing they could assign me with for the remainder. Within almost four months of my joining, the company realised its folly of over-hiring, even as it faced serious attrition at the managerial level.

I was soon relocated to the HR (human resources) division, to be looked down upon by the self-perceived office smartasses. Neither my Engineering degree nor my Development Studies degree had any contributions to make in this new role. Many, from even within the office, suggested resignation. However, I decided to put myself through it. This was around the time the one-year-old company was formulating many of its HR policies, given my interest in labour studies, this seemed to me, an educating experience.

The word “labour” and “workmen” were to be used with a lot of caution, if not, completely avoided in the policy documents. This was important, as law dictated rights be available to labour. Funnily, the word aroused emotions bordering on contempt among many, as if it relegated us to an undesirable position. This was not specific to my office, even in general, people in these circles refused to be thought of as workers or labourers. We were above them. Nobody “worked” anymore, “resources were allocated to tasks”, working hours didn't matter as long as we had “bandwidth”, there was no need for organising, as we could just as well “synergise and leverage”, and if that didn't work, we could just “circle back”.

This distinction between “us” and “them” was deemed quite important. But we all fused into one homogeneous mass on the roads, at vegetable shops, the bus stops and the railway stations; whereas our bosses sped past us in their luxury SUVs.

Timely performance award ceremonies, office parties, possibility of overseas posting, and other forms of HR intervention kept employee resentment in check. Everyone's allegiance was to the bosses, the company and its performance. But funnily enough, we had more in common with the security staff and janitorial staff, who, like us, were also temporary workers, with no job security.

Second, solidarity even among the white collar workers was absent to the extent that one could not confide concerns to a colleague in the next desk, without the fear of being reported to the management for extra brownie points.

We were still debating whether the company needed a work-life balance policy when the news of the EY employee’s suicide took social media by storm. Inner HR circles sympathised with EY for the bad publicity the dead employee’s mother caused them.

It was finally decided that a work-life balance policy had no place in a consultancy firm where time was money. Working during the weekends was considered an aspirational goal, and a special privilege afforded to the boss’s favorites. If you weren’t working beyond office hours, you were not working enough. There was no question of overtime pay, with the unspoken rule being that our high salary already paid for all the overtime work.

Additionally, if one had to work beyond the stipulated hours, one was just not efficient enough and could soon be put on a PIP (Performance Improvement Plan). A six-month PIP can convert into a dismissal if deemed necessary by the management. Being on a PIP, needless to say, was deeply humiliating, and more importantly very anxiety-inducing. Many often quit while on PIPs.

My final set of tasks included creating story boards to educate the employees on company values of which there were quite a few, but in summary said the same thing -- work hard and the company will be rewarded, and you in turn will get to keep the job. Several of them glorified over-working through stories of multi-tasking employees, employees who worked round the clock, and worked on unrealistic deadlines.

These comic strips were to be displayed on a TV at the office to boost employee morale, and guide them towards further self-exploitation, should they begin to question it all.

I quit the job after seven months of joining with a life-time supply of corporate experience. My experience, of course, is not specific to the company or the city, or a particularly new revelation in any sense.

My friends in Bengaluru have shared scarier stories of retrenchment, over-work and exhaustion. These included WFH (work from home) employees who were suddenly logged out of the company networks, fired employees who were escorted through the backdoor so that their colleagues don't see them crying, employees who were fired two months after a promotion and so on. None of them, however, have ever spoken (or were possibly even aware) of the successful organisation efforts led by IT/ITes employees in the city, nor have they seemed to identify with their cause. Unionisation was always thought to be the resort of the toiling masses, a category they could never put themselves in.

Mumbai, despite its rich history of working-class movements, has so far steered clear of any such (successful) attempts by its burgeoning white collar workers (who refused to see themselves as part of the working class). Its seemingly woke crowd is a sorry, largely apolitical mess, that has so far proven incapable of such political organising.

Karnataka’s retraction of a similar proposal was achieved following efforts led by KITU (Karnataka IT/ITeS Employees Union) . In the absence of a concerted working-class movement, Maharashtra can and will boldly go forward with this retrogressive policy that negates centuries of proletarian struggles, even as the rest of its employees continues various forms of “strategic re-alignments”, fashioning new “KPIs” to enhance “ROIs”, and gladly welcome the return of the long working day.

The writer is a PhD scholar at the Centre for Development Studies, Trivandrum. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.