India’s Crony Corporate State and the Anatomy of Inequality

File Photo

India’s adoption of the Western liberal economic model has positioned it as a junior partner to Western multinational corporations (MNCs), but unlike many European countries that coupled liberalization with robust social safety nets, India has largely failed to develop such protections for its population. This contrast is critical in understanding India’s socio-economic challenges today.

European nations completed their industrialisation by systematically dismantling feudal structures while establishing extensive social welfare programs—including public healthcare, universal education, pensions, and insurance schemes—which ensured broad-based societal benefits from economic progress. These measures created a foundation for social stability, increased human capital, and equitable distribution of growth dividends.

In contrast, India’s ruling class—comprising entrenched big corporate interests allied with feudal and communal forces—has aggressively pushed liberalisation and privatisation without embedding fairness, transparency, or accountability mechanisms. The dismantling of state-owned public sectors such as healthcare, education, railways, and even defence has weakened the state’s capacity to provide essential services and safeguard citizens’ welfare.

The Indian corporate sector's focus remains narrowly centred on profit maximization rather than fostering scientific and technological innovation or generating inclusive economic opportunities capable of driving societal transformation. Consequently, the promises of liberalisation have not translated into comprehensive development for India’s vast population.

The government has increasingly relied on external debt, borrowing approximately US$ 2.62 trillion against a GDP of about US$ 2.8 trillion (data from the World Bank and IMF), which places a significant fiscal burden on the nation. Meanwhile, unemployment rates especially among educated youth are alarming, with approximately 83.6% reported as unemployed, indicating a severe mismatch between education and job creation.

Rural poverty and social exclusion persist deeply, forcing over 100 million people to migrate to urban and metropolitan centers like Delhi, Mumbai, and Kolkata. These migrants often settle in severely inadequate slum conditions and work predominantly in the informal and unorganized sectors—as domestic workers or street labourers—where wages are minimal, and labour rights are frequently ignored.

A Liberal Dream Turned Crony Reality

When India embarked on economic liberalization in 1991, it heralded a new dawn of market freedom and global integration. The dismantling of the License Raj, once seen as a necessary evil, was celebrated as the first major step toward modern capitalism. The promise was clear: free markets would unleash entrepreneurship, foreign investment would spur innovation, and economic efficiency would replace bureaucratic stagnation.

More than three decades later, the results are paradoxical. India has become one of the fastest-growing major economies in the world, yet it is also one of the most unequal. The liberal dream, once driven by hopes of broad-based prosperity, has morphed into a crony corporate-led regime that rewards proximity to power rather than productivity.

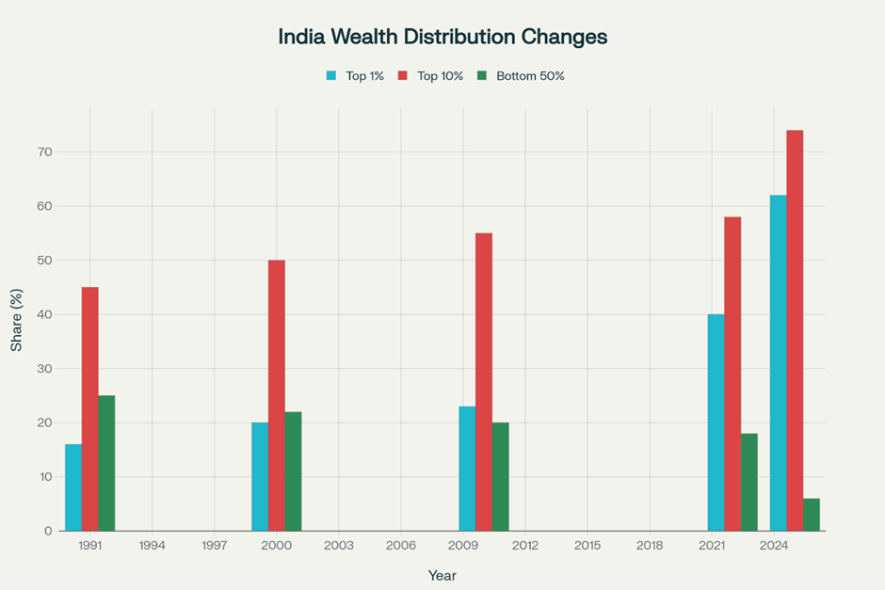

According to the World Inequality Lab (2025), the richest 1% of Indians now control 62% of the nation’s wealth, while the top 10% accounts for 74%. The bottom half of the population, numbering over 700 million people, share a meagre 6%. Behind the glossy GDP numbers lies a grim economic and social imbalance that threatens the very ideals liberalization once promised.

The Genesis of Crony Capitalism

The roots of India’s crony capitalism lie in the very process of liberalisation itself. The early 1990s reforms—championed by then Finance Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh—were aimed at dismantling state monopolies, encouraging competition, and integrating India into the global market. However, while these reforms succeeded in attracting capital, they failed to build robust regulatory institutions capable of curbing elite capture.

The withdrawal of the state from production did not mean its withdrawal from power. Instead, the state became a selective enabler—granting licenses, contracts, and clearances to business conglomerates with political access. This pattern of “policy patronage” replaced the old bureaucratic controls with a new nexus between political elites and corporate capital.

This juxtaposition of Western-style liberal economic policies without comparable welfare frameworks has created a profound socio-economic crisis in India.

The Numbers Behind Inequality

In 1991, when reforms began, the top 1% of earners held about 16% of national wealth. Over the next three decades, that share nearly quadrupled. Meanwhile, the bottom 50% saw their wealth decline sharply—from 25% to just 6%.

The data tells a story of structural exclusion. As India’s economy expanded from $270 billion in 1991 to over $3 trillion in 2025, the rewards of growth became heavily skewed. The benefits of liberalization—foreign capital, high-end jobs, and stock market gains—remained concentrated in urban and corporate circles, while rural incomes stagnated.

Economists argue that inequality in India is not merely an economic outcome but a policy design feature—a product of deliberate choices that privilege corporate capital and suppress redistributive justice.

When the State Serves the Few

India’s crony economy thrives on the interdependence of politics and business. This nexus is not hidden; it is institutionalized through opaque political financing, regulatory discretion, and selective privatization.

High-profile scandals such as the 2G spectrum allocation (2010), coal block allocations, and more recent banking and infrastructure scams have revealed how public resources were channeled toward politically connected entities.

“Crony capitalism is not a side effect—it is the operating system of India’s neoliberal model,” argues V.R. Suryawanshi (2025) in his study on public policy and corporate influence.

Public-private partnerships, meant to boost infrastructure and investment, often turn into conduits of state capture. Major industrial houses expand into multiple sectors—from ports and power to telecom and finance—often aided by policy favors or regulatory exemptions.

The Competition Commission of India (CCI) and Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI), established to ensure fair competition, frequently face funding shortages and political interference, weakening their oversight capacity.

The Political Economy of Inequality

The concentration of wealth has far-reaching political consequences. As corporate power grows, so does its influence over electoral politics. The introduction of electoral bonds—a mechanism for anonymous political donations—has further deepened opacity, allowing large corporations to fund ruling parties without public scrutiny.

This creates a feedback loop: money buys policy, policy enriches donors, and donors fund political power. The outcome is a democracy tilted toward those who can afford to finance it.

Economist Joseph Stiglitz (2012) calls this “the rentier society of the 21st century”—where those who control assets and access, rather than those who create value, accumulate disproportionate wealth. In India, the rent-seeking logic of capitalism has penetrated the political process itself.

Growth Without Inclusion

On paper, India’s growth story is spectacular. The IT revolution, the boom in services, and rising foreign direct investment have transformed cities like Bengaluru, Hyderabad, and Gurgaon into global business hubs. Yet, this transformation has bypassed much of the population.

Rural distress, stagnant real wages, and unemployment remain chronic. Between 2011 and 2025, the bottom 50% of Indians saw their average income rise by less than 2% annually, while the top 1% saw increases of over 12% per year (World Inequality Report, 2025).

This lopsided growth pattern has led to a hollowing out of the middle class—once the aspirational engine of India’s post-liberalization narrative. The gap between rural and urban India, formal and informal sectors, and capital and labour has never been wider.

Meanwhile, social spending as a share of GDP remains low. India spends only 2.1% on healthcare and 2.9% on education, far below comparable emerging economies.

Theoretical Framework: Cronyism as Structural Capture

The phenomenon of crony capitalism can be explained through two interrelated frameworks:

-

Crony Capitalism Theory (Haber, 2006):

It posits that when business success depends on political favour rather than competition, economic growth becomes unstable and inequitable. Over time, such systems foster monopolies, deter innovation, and erode public trust.

-

State Capture (Hellman, Jones & Kaufmann, 2000):

In this framework, private entities influence policymaking, legal frameworks, and regulation to serve their interests. This “capture” weakens democratic institutions and diverts resources from public to private ends.

Together, they explain how India’s neoliberal state evolved from a regulator to a broker—a facilitator of private wealth accumulation through selective policy intervention.

The Social Consequences

The effects of inequality go beyond economics. Rising disparities have eroded social cohesion, trust in governance, and intergenerational mobility.

As wealth clusters in fewer hands, political polarization and populist politics rise in response to social frustration.

Urban India faces an emerging underclass of underemployed youth, while rural India continues to rely on precarious migration for survival. The promise of “New India”—a nation of digital innovation and middle-class dreams—exists alongside the reality of agrarian distress, jobless growth, and urban poverty.

Sociologists warn that this duality could fuel long-term instability. “Economic exclusion breeds political alienation,” writes C. Sen (2024) in his Azim Premji University Working Paper. “The legitimacy of democracy weakens when prosperity is visible but inaccessible.”

Breaking the Cycle: Towards Inclusive Capitalism

The challenge before India is clear: to reconcile growth with equity, capitalism with accountability, and markets with morality. To achieve this, a multidimensional reform agenda is needed.

1. Transparency and Anti-Corruption Frameworks

Strengthen anti-corruption laws and digitalize all public procurement and privatization processes. Transparency must become the norm, not the exception.

2. Empowering Regulators

Regulatory institutions must be granted genuine autonomy, secure funding, and legal authority to prevent monopolistic behaviour and cartelization.

3. Progressive Taxation

Reintroduce wealth and inheritance taxes on ultra-rich individuals and corporations, and close loopholes in capital gains taxation to ensure fair redistribution.

4. Political Finance Reform

Abolish opaque electoral bonds and mandate full disclosure of corporate donations. Political competition should be rooted in ideas, not in financial muscle.

5. Social Investment

Increase public spending on education, healthcare, and rural development. Human capital must become the foundation of sustainable growth.

6. Support for SMEs and Local Enterprises

Provide credit and infrastructure support to small and medium enterprises—the real drivers of employment and innovation.

Reclaiming the Liberal Promise

India’s liberalisation project was conceived as a transformative vision—one designed to unleash entrepreneurial dynamism, foster innovation, and build a globally competitive economy. In many respects, that vision materialized; yet, its rewards have been disproportionately captured by a privileged ruling elite, entrenched at the intersection of political and corporate power. The market, once imagined as an instrument of empowerment for the many, has instead consolidated the dominance of a new oligarchy—an alliance of capital and governance that thrives on exclusion.

This reality underscores an urgent need for policy recalibration—one that restores the moral equilibrium between profit and people. Economic liberalization must now be complemented by a renewed commitment to social safety nets, equitable public investment, and the generation of dignified employment opportunities. These are not adjuncts to growth; they are its ethical foundations.

India’s developmental trajectory must learn from inclusive growth models elsewhere—most notably China, which within three decades, managed to integrate rapid industrial expansion with broad-based poverty reduction. For India, the challenge lies not in growth itself, but in ensuring that its dividends reach the marginalized rural and urban poor who remain excluded from its promise.

The future of India’s democracy and economy hinges on reconciling growth with justice. Without structural reform and institutional accountability, the liberal dream risks collapsing under the unsustainable burden of inequality.

To reclaim that promise, India must move beyond crony capitalism toward a model of inclusive and sustainable socialism—a system grounded in collective cooperation, transparency, and social welfare as its guiding objectives. Such a transformation would redefine economic success not by the accumulation of wealth, but by the equitable distribution of opportunity.

Only then can the world’s largest democracy fulfill the emancipatory vision that liberalization once embodied: freedom not merely for capital, but for its people.

Author’s Bio: Akhilesh Chandra Prabhakar is an International Professor of Economics. He also serves as the Director of Global South Social Networks and a researcher of Sustainable Economic Development and the Political Economy of the Global South.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.