Communalism to Corporate Order: Unmasking Nexus of Power, Profit, Propaganda

Image for representational purpose.

The contemporary political economy of India presents a paradox that demands urgent scholarly attention. A nation that emerged from colonial subjugation with constitutional commitments to ‘secular democracy, ‘social justice, and ‘socialism’ (a socialist pattern of society with providing equitable developmental opportunity to all citizen) has increasingly become the site of a peculiar convergence: the deliberate fusion of communal ideologies with corporate capital accumulation, orchestrated through sophisticated mechanisms of media manipulation and institutional capture.

This article examines how this convergence—the nexus of communalism and corporate order—has systematically remade India's political, economic, and cultural landscape over the past few decades, transforming it into a crony corporate-led Brahmanical socio-economic-cultural order on the name of Hindutva Rashtra.

The transformation is neither accidental nor inevitable. Rather, it represents the strategic deployment of communal polarisation as a tool to facilitate unimpeded corporate expansion and state capture.

This nexus operates through three interlocking mechanisms: First, the capture and control of policy formation through constitutional and legislative reform. Second, the infiltration of administrative institutions and the appointment of ideologically aligned actors to key decision-making positions; and third, the systematic dismantling of accountability institutions—the judiciary, media, and progressive liberal democratic and secular people’s organisations and political parties—that might otherwise expose or resist these processes.

What distinguishes this contemporary formation from earlier authoritarian experiments is its ideological sophistication: it legitimises corporate plunder and wealth concentration by channeling popular grievances toward religious and cultural antagonisms, thereby fracturing the very class consciousness that might generate resistance to economic exploitation.

The scale of this transformation is reflected in stark economic indicators. The top 1% of India's population now controls 62.1% of national wealth, while the bottom 50% survives on a mere 6.4%. This inequality has surpassed levels witnessed during the colonial era—a bitter historical irony that suggests India has regressed from post-independence promises of economic justice.

The concentration of wealth has been accompanied by parallel concentrations of corporate power. Large industrial houses have consolidated monopolistic control over critical sectors—telecommunications, energy, retail, media—while small and medium enterprises face systematic disadvantage.

This economic consolidation mirrors political consolidation: a handful of corporate conglomerates, intertwined with political authority, now determine which sectors receive state investment, which laws are enacted, and ultimately, whose interests are served by the apparatus of the state.

Yet this corporate hegemony could not have been consolidated without ideological work. The legitimation of neoliberal policies that favour wealth concentration and the erosion of labour protections required a cultural narrative more compelling than technical economic arguments about efficiency and growth. The solution emerged from the systematic mobilisation of communal ideology—specifically, the Hindu nationalist vision of a unified Hindu Rashtra—as the organising principle of political life.

By framing economic transformation within narratives of cultural nationalism, civilisational pride, and religious identity, the corporate-communal nexus has managed to recruit masses of supporters for policies that objectively work against their material interests. The construction of internal enemies—religious minorities, secular intellectuals, labour unions, environmental activists—became a technique for managing consent, deflecting attention from the machinery of wealth extraction operating in plain sight.

The role of propaganda and media capture in sustaining this architecture cannot be overstated. India's media landscape has undergone a fundamental transformation, shifting from a diverse ecosystem of competing narratives to an increasingly consolidated structure dominated by a handful of corporate conglomerates with extensive business portfolios dependent on government favours. These media organisations amplify State and corporate narratives while marginalising critical inquiry.

Major broadcasting networks have systematically promoted communal divisions, disseminated misinformation aligned with ruling party interests, and silenced investigations into corporate malfeasance and state corruption. This media capture operates as soft censorship: journalists, editors, and producers internalise government preferences through economic incentives rather than overt coercion. The result is a public sphere increasingly hollowed of genuine deliberation, replaced by a managed spectacle of nationalist fervour and religious antagonism.

Historically, India’s political economy has experienced several crucial transitions. The colonial period established extractive economic structures that drained wealth while fragmenting indigenous industries. Post-Independence, Jawaharlal Nehru's developmental State attempted to reverse this through State-led industrialisation, a mixed economy, and the creation of public sector enterprises. For nearly four decades, this model—however imperfectly—maintained the State's primacy over private capital.

The neoliberal revolution initiated in 1991, however, fundamentally inverted this relationship. Capital, once subordinate and nationally embedded, became dominant and internationalised. The State, transformed from guardian of development to servant of corporate interests, began evaluating itself against criteria set by capital rather than by constitutional obligations to its citizens.

This transition was not inevitable. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, significant portions of India's industrial elite expressed skepticism toward rapid liberalisation, forming organisations like the Bombay Club to advocate for gradual, cautious approaches to market opening. Yet, over time, as foreign investment accelerated, new export opportunities emerged, and regulatory controls diminished, a critical section of the Indian bourgeoisie shifted position. They recognised that neoliberalism, rather than threatening their interests, offered unprecedented opportunities for profit, consolidation, and global expansion.

The manufacturing of consent for neoliberalism proceeded through conventional channels—business associations, policy intellectuals, international financial institutions. But as resistance to inequality and corporate domination grew, particularly after the 2008 financial crisis exposed the vulnerabilities and inequities of liberalised markets, a new technology of consent was required. This is where the communal-corporate nexus became indispensable.

The Hindu nationalist Right, embodied in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and its political organisation, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), represented a powerful ideological apparatus with mass mobilisational capacity accumulated over decades. What had previously seemed like parallel projects—corporate profit maximization and communal nation-building—could be synthesised.

Corporate interests discovered in Hindu nationalism a cultural framework capable of mobilising support for anti-labour, pro-privatisation policies. Hindu nationalism discovered in corporate capitalism the resources to expand its organisational reach and media presence. The alliance proved mutually reinforcing: communal narratives justified corporate expansion by framing it as national self-reliance and civilisational assertion; corporate resources and State machinery amplified communal messaging through media control and institutional capture.

This nexus has produced consequences visible across multiple dimensions of Indian life. Labour protections have been systematically weakened through legislative reform, transforming the workforce into a precariat of contract and casual workers. Agricultural policies favouring agribusiness have driven peasants into debt and destitution. Education and healthcare systems, underfunded through regressive taxation policies, deteriorate as private institutions expand to serve the wealthy.

Environmental protections yield to corporate resource extraction. Civil liberties face unprecedented restrictions justified through security and national interest rhetoric. Yet each of these assaults is framed—through managed media narratives—as necessary for national progress, religious protection, or patriotic duty.

The convergence of communalism and corporate order represents, therefore, a distinctive historical formation. It is neither fascism in the classical European sense, nor simple authoritarianism. Rather, it constitutes a hybrid form specifically adapted to post-colonial conditions: one that weaponises democratic forms while hollowing their substance, that employs cultural nationalism to legitimise economic plunder, and that systematises the capture of state institutions at every level—legislative, administrative, and judicial—to serve narrow corporate and ideological interests. Understanding this formation requires analytical tools adequate to its complexity: we must comprehend both its economic logic—the accumulation strategies and monopolistic consolidation that drive it—and its ideological machinery—the narratives of nationalism, civilisational pride, and religious identity that generate mass consent for policies that undermine human welfare.

This study traces the historical consolidation of the communal–corporate nexus as an outgrowth of the contradictions inherent in neoliberal capitalism and the deepening crisis of traditional modes of bourgeois legitimation. It interrogates the processes through which communal ideology is appropriated, reconfigured, and ultimately deployed as a mechanism for corporate appropriation and accelerated accumulation. It further documents the systematic capture and reorientation of key democratic institutions—including the media, the judiciary, and the administrative state—toward the reproduction of this nexus. In doing so, it elucidates how propaganda is engineered not merely as an adjunct to political power, but as a foundational infrastructure indispensable to sustaining this emergent authoritarian formation.

Crucially, the study resists framing these developments as either deterministic or irreversible. By uncovering the material interests, institutional logics, and coercive-consensual mechanisms that uphold the nexus, the research seeks to contribute to the articulation of counter-hegemonic political projects capable of defending democratic principles, reclaiming the emancipatory potential embedded within India’s constitutional order, and forging new pathways toward substantive equality and genuine collective self-determination.

The stakes of this inquiry extend well beyond the confines of academic debate. The trajectory of the communal–corporate nexus in India mirrors—and in certain respects anticipates—political-economic transformations visible across the globe, from Hungary and Poland to Brazil and other contemporary authoritarian-capitalist formations. In each case, convergences between ethno-nationalist ideology and neoliberal economic restructuring have facilitated the capture of state institutions and the reconfiguration of political economies in profoundly unequal and exclusionary directions.

A rigorous understanding of the Indian case thus illuminates broader global dynamics of 21st century authoritarian capitalism, offering insights essential for defending democratic institutions and reimagining egalitarian futures across diverse social and geopolitical contexts.

-

The top 1% controls 62.1% of wealth while the bottom 50% holds only 6.4%, according to the World Inequality Database 2024 and research cited in financial analysis of India's wealth distribution crisis.

-

Large industrial houses have consolidated monopolistic control through neoliberal policies that have created structural dependencies between corporate interests and state actors, enabling indirect control of key sectors and policy decisions.

-

Media conglomerates like Network18 (owned by Reliance Industries) exemplify how corporate ownership creates structural dependencies that influence editorial decisions, allowing governments to indirectly control narratives through these consolidated media structures.

-

The relationship between State and capital fundamentally shifted under neoliberalism, transforming capital from a subordinate, nationally defined entity into a dominant, internationalised force that now evaluates state compliance rather than the reverse.

Emergence of Fascist Modi & Modinomics

The contemporary Indian story is both compelling and deeply troubling. Former Gujarat minister and BJP–RSS leader Shankersinh Vaghela’s statements alleging that the 2002 Godhra train burning was a “staged act” have reignited old debates about State complicity in communal violence. These claims—whether politically motivated or revealing deeper truths—gain urgency in light of Modi’s long ascendancy from Gujarat’s Chief Minister to India’s Prime Minister. Against the backdrop of widening social divisions, corporate consolidation, and democratic regression, the need for scrutiny has never been greater.

Godhra and Its Political Aftermath

On February 27, 2002, coach S-6 of the Sabarmati Express was set on fire near Godhra, resulting in the deaths of 59 Hindu pilgrims. The incident triggered statewide communal violence that killed at least 1,044 people, according to official figures (government of Gujarat report, 2002), though several independent studies including the Concerned Citizens Tribunal (2002) and Human Rights Watch (2003) estimated fatalities between 2,000–3,000, most of them Muslims. Over 150,000 people were displaced.

Subsequent judicial proceedings, including the Nanavati-Mehta Commission (2014), upheld the view that the attack was premeditated by local Muslims; yet independent journalists (Siddharth Varadarajan, The Times of India, 2002; The Caravan, 2024) and human rights groups have identified inconsistencies in the official narrative. Vaghela’s 2024 claim that the event was orchestrated to consolidate Hindutva leadership over Modi’s rivals, such as Pravin Togadia, revisits an old fault line in Gujarat’s political history.

Far from distancing himself from the violence, Modi’s government organised public yatras and events that, according to Tehelka (2007) sting operations and Outlook India (2002), celebrated “Hindu pride” in the aftermath, turning communal trauma into political capital.

Precedents of Organised Communal Violence

The Godhra conflict fits a larger historical pattern. Between 1989 and 1993, the BJP and affiliates of the Sangh Parivar, including the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and Bajrang Dal, mobilized around the Ram Janmabhoomi movement. Riots in Meerut, Bhagalpur, Mumbai, and Ayodhya led to approximately 9,000–10,000 deaths (Varshney, 2002; Engineer, 1995). The Babri Masjid demolition in December 1992 represented a strategic shift—religious nationalism became the axis of political mobilisation that challenged India’s secular democratic foundation.

Economic Alliances and Corporate Power

Modi’s transformation from a regional leader to a corporate-backed national figure emerged through the Vibrant Gujarat Summits (2003–2013). The 2011 summit, in particular, saw Mukesh Ambani (Reliance Industries) and Gautam Adani (Adani Group) praising Gujarat’s pro-business model, which became the ideological and financial springboard for Modi’s national campaign (Jenkins, 2014; Chhibber & Verma, 2018).

Following this, Union Home Minister Amit Shah was deployed to Uttar Pradesh to replicate Gujarat’s model of cultural polarisation. Subsequent riots in Muzaffarnagar (2013) left 62 dead and over 50,000 displaced (NHRC & Amnesty International, 2013). BJP MLA Sangeet Som, named in police chargesheets, was publicly felicitated by Modi at later rallies, symbolising the political sanctioning of majoritarian mobilization.

Media Consolidation and Information Warfare

Between 2012 and 2014, corporate-media alliances played a pivotal role in crafting the Modi narrative. Groups like Network18 (Reliance), Zee Media (Essel Group), and Adani Enterprises either directly supported or acquired media outlets (Nilekani, 2023). Election Commission data shows over ₹15,000 crore spent on publicity and rallies across 5,000+ events during the 2014 campaign—one of the world’s costliest democratic exercises (CSDS, 2015). Corporate defection funding and ideological alignment tilted news coverage decisively in favour of BJP narratives (Thakurta, 2015).

Crony Capitalism and Economic Exclusion: Bank Write-offs and Corporate Gains

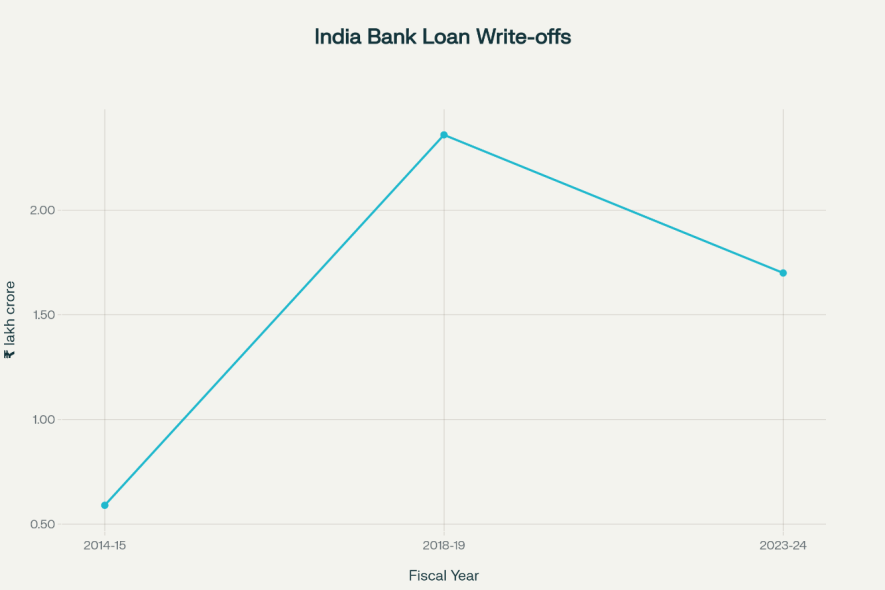

Indian banks wrote off ₹16.35 lakh crore in bad loans from 2014–2024, as per the RBI and Finance Ministry, with the highest annual write-off at ₹2.36 lakh crore (FY19). Thus, other types of special benefits, including tax relief, official RBI and Finance Ministry data (2023) show ‘corporate loan write-offs have crossed totalling over ₹25 lakh crore, benefitting conglomerates such as Adani, Ambani, Vedanta, and Essar.

Indian Bank Loan Write-Offs (₹ Lakh Crore) 2014-2024

Corruption reporting

-

Land acquisition and leasing policies increasingly favour corporates; long-term leases and asset transfers often involve land initially owned by marginalised communities.

-

Reports indicate that benefits from these disposals accrue predominantly to groups such as Adani and Ambani, who have received favourable lease terms and been major beneficiaries of policy changes.

Simultaneously, India’s share of manufacturing employment fell from 12.6% (2012) to 10.2% (2023) (CMIE, 2024). The Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR, 2023) and the World Inequality Lab report (2025) clearly say that wealth inequality reached record highs: the top 1% controls 62% of total wealth, while the bottom 50% own only 6%.

India’s total external debt stood at $663 billion by March 2024 (World Bank Data), while combined IMF-World Bank exposure surpassed $2.5 trillion when including private external liabilities.

Informal Economy and Unemployment

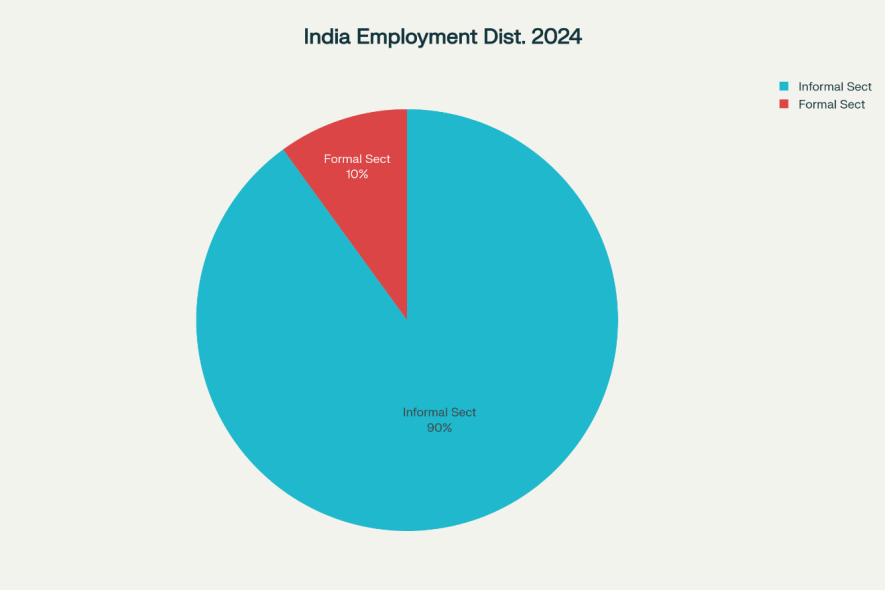

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) and Indian government data confirm that approximately 90% of India's workforce is in the informal sector, lacking job security and social protections; these workers mostly earn below statutory minimum wages. According to the ILO and India Employment Report (IHD–ILO, 2024), approximately 90% of India’s workforce remains in the informal sector, lacking job security and social protection. Furthermore, 40.8% of regular workers and 51.9% of casual workers earn below the average daily minimum wage (ILO/IHD, 2024). Youth unemployment remains alarming—about 83% of India’s unemployed are youth, highlighting structural issues in education and labour-market linkage (ILO, 2024). Youth unemployment reached 83% among educated jobseekers (CMIE, 2024).

Figure 1: Estimated Informal vs Formal Workforce (India, 2024)

Source: ILO, IHD–ILO India Employment Report 2024.

Distribution of Workforce: Informal vs Formal Sectors in India (2024)

Unemployment among educated youth remains a structural challenge: the ILO's India Employment Report 2024 pegs youth unemployment at 83% of all unemployed, with urban unemployment for the educated exceeding 26%.

Malnutrition and Food Insecurity

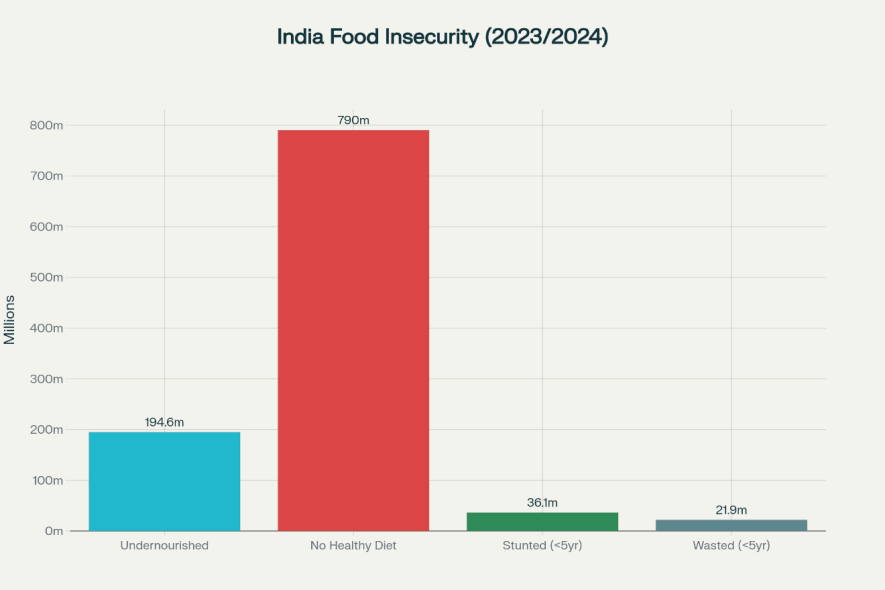

India has the largest number of undernourished people globally (194.6 million), with more than 790 million unable to afford a healthy diet (SOFI/FAO, 2024); child malnutrition also remains extremely high, with 31.7% of children stunted and 18.7% wasted.

Meanwhile, the United Nations’ State of Food Security and Nutrition report (SOFI, 2024) estimated that around 194 million Indians remain undernourished, not one billion as often exaggerated. The World Bank (2024) estimates that roughly 129 million Indians live below the international poverty line of $2.15 per day.

As per the World Bank's updated poverty line ($2.15/day), India’s poverty rate has dropped to 2.3% (2022). However, under the more widely used “lower-middle-income country” poverty line ($3.65–$4.20/day), roughly 24% of Indians—over 300 million people—remain in poverty. Rural poverty is much higher, and food insecurity affects between 194.6 million (undernourished) and 790 million (unable to afford a healthy diet).

The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5, 2019–21) shows 35.5% of children under five remain chronically malnourished.

Malnutrition and Food Insecurity in India (2023/2024)

-

One billion people are not classified as “poor” under international thresholds, but the majority experience some form of deprivation or malnutrition—especially among tribal, Dalit, and minority populations.

More than half (55.6%) of Indians cannot afford a balanced diet, and over 300 million people regularly face food insecurity.

GDP, Debt, and Privatisation

-

India’s nominal GDP is just under $3 trillion as of 2024, with government debt rising to $2.14 trillion (57% of GDP), and total public and private external exposure around $2.62 trillion.

-

Public sector investment has declined, with privatization and corporatization at the heart of policy decisions since 2014.

Corruption and Resource Extraction

-

Significant scandals, including the ₹62,000 crore “energy scam” exposed by R.K. Singh, have involved deals that transfer major public resources to corporate interests through allegedly inflated or questionable contracts.

-

The open-door policy for foreign multinationals has deepened resource and labor exploitation, undermining local self-reliance and development.

Social Costs and Decline of Welfare

Price deregulation of essentials, withdrawal of subsidies, and privatization of health and education have intensified economic hardship. The State of Inequality in India Report (NITI Aayog, 2022) found the bottom 20% of Indian households control only 3% of the national income. A UNDP report (2023) noted that multidimensional poverty in eight Indian states rivals sub-Saharan levels, with Bihar (52%), Jharkhand (43%), and Uttar Pradesh (36%) leading in deprivation. More than 300 million Indians face food insecurity (Global Hunger Index, 2023), while enforcement of minimum wage laws remains weak.

Internal migration due to agrarian decline has accelerated, with over 450 million internal migrants recorded in the Census 2011, projected to surpass 600 million by 2025 (IIPS & World Bank projections, 2024).

Spectacle, Faith, and the Retreat of Science

Public expenditures on cultural-religious spectacles—such as the Ram Mandir project (₹1,800 crore) and Kumbh Mela (₹4,200 crore)—contrast starkly with underfunded public universities and hospitals. The Prime Minister’s 92 foreign trips between 2014–2023 cost taxpayers ₹5,455 crore (MEA response to Parliament, 2023), reflecting priorities skewed toward optics over outcomes. During the COVID-19 pandemic, The New York Times (July 2021) and The Lancet (May 2021) estimated excess deaths in India between 3.5–4.7 million, with health infrastructure collapse most severe in Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat.

Democracy in Decline

India’s democratic regression has drawn international concern. The V-Dem Institute (2024) classifies India as an “electoral autocracy”, while Freedom House (2023) downgraded India’s rating to “partly free.” The Editors Guild (2023) and Reporters Without Borders (2024) cite increased censorship, online surveillance, and criminal cases against journalists critical of the regime. Parliament’s legislative functioning has weakened, with ordinance usage tripling since 2014 and debates curtailed to record lows (PRS Legislative Research, 2024).

Toward a Just and Inclusive India

The tragedies of Godhra, Muzaffarnagar, and Ayodhya remind the nation that communal division and corporate enrichment cannot form the foundation of a just democracy. India’s path forward requires reclaiming secular constitutionalism, redistributive economics, and rational public discourse. As Ambedkar’s warning in the Constituent Assembly reminds us, political democracy cannot survive without social and economic democracy.

India’s youth deserve employment and dignity over propaganda; its labourers require rights, not precarity; its marginalized citizens deserve protection, not scapegoating. The moral question confronting the republic remains urgent: Can India survive without justice, inclusion, and truth?

The writer is an International Professor of Economics. He also serves as the Director of Global South Social Networks and a researcher of Sustainable Economic Development and the Political Economy of the Global South. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.