Baghdad to Caracas: Washington Manual on Sanctions & War

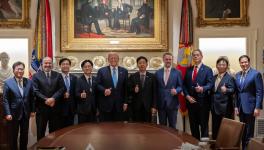

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio with the former commander of SOUTHCOM Alvin Holsey. Photo: Secretary of State / X

Over the last several weeks, Washington has escalated threats and hostilities against Venezuela, and US President Donald Trump openly confirmed that he authorized the CIA to carry out covert action against the country. These actions are concerning and represent a serious intensification of the war drive against the Caribbean country, and they also confirm what many have been saying for years, the US is heavily invested in what happens in Venezuela and is not afraid to use all tools at its disposal to impose its interests.

“Can anyone really believe the CIA hasn’t already been operating in Venezuela for 60 years?” Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro asked, after Trump announced the authorization of CIA activity in his country.

The answer, when viewed through the historical record of two centuries, confirms a pattern of continuous interference aimed at asserting US dominance over the entire hemisphere. The escalating threats of war emanating from the Trump administration against Caracas represent not a new policy, but the culmination of a longstanding project of regime change, one that bears profound and disturbing similarities to the drive for war against Iraq under the Bush administration.

Washington has always viewed Latin America and the Caribbean through the lens of the Monroe Doctrine, unilaterally reserving the region for US geopolitical dominance. The last two hundred years confirm a pattern of repeated, aggressive intervention. The most notorious recent examples, where US involvement spanned political support, intelligence operations, and direct military intervention, include the 1954 coup against Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala, the 1965 invasion of Dominican Republic that thwarted the return of a progressive government led by Juan Bosch, the 1973 coup that dismantled Salvador Allende’s socialist project in Chile, the 1983 plot to overthrow the government of Maurice Bishop and the invasion of Grenada, and the repeated overthrow of Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 1991 and 2004. The 2009 coup in Honduras against the government of Mel Zelaya continued this tradition.

However, Venezuela has become the definitive target, facing more US-backed attempts at regime change than any other Latin American country in the last quarter-century. The obsession with reclaiming control over the country began shortly after Hugo Chávez’s election in 1998, a victory that signaled a radical shift away from US-sponsored neoliberal policies and the beginning of a period of major transformations from poverty reduction to regional integration led by a wave of left governments in Latin America. Washington actively supported numerous efforts to remove Chávez, notably a military coup in 2002 that was defeated by a mass uprising and the crippling 2002–2003 oil lockout aimed at shutting down the country’s most important source of revenue.

Under both George W. Bush and Barack Obama, millions of dollars were funneled to drive Venezuela’s right-wing groups, often lacking a social base, into direct confrontation with the Venezuelan government through tactics that ranged from assassination plots to terrorist actions. This funding stream supported groups and leaders who, while posing as democratic opposition or non-governmental organizations, have consistently advocated for the violent removal of the country’s democratically elected government. One notable recipient of US funds, María Corina Machado, the far-right leader who was recently awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, built her political career on decades of advocacy for US and Israeli foreign intervention.

The pattern of support for regime change continued after Chávez’s suspicious death in 2013, which prompted many to wonder about a CIA plot. After the election of Nicolás Maduro, the Obama administration backed a violent protest wave in 2014, called guarimbas, marked by racist lynchings of Black supporters of the government by right-wing mobs. Maduro faced another sustained period of US-backed violent protests in 2017. A 21-year-old Afro-Venezuelan Orlando Figuera, was attacked and burned alive in Caracas by opposition activists in May 2017.

Economic siege intensified

In 2015, President Obama escalated rhetorical and economic pressure by declaring Venezuela an “extraordinary and unusual threat to US national security.” This charge was widely recognized as having no factual basis and was initially rejected even by some Venezuelan opposition leaders. Yet, the declaration provided the legal pretext for the imposition of sanctions, which initiated the collapse of the oil industry and devastated the Venezuelan economy.

Within a year of Trump’s first term, the US imposed even harsher sanctions, directly targeting Venezuela’s oil sector. Prior to the 2017 sanctions, the average monthly decline in oil production was approximately 1%. Following the August 2017 executive order to block Venezuela’s access to US financial markets, the rate of decline plummeted, falling at more than three times the previous rate. The August 2019 sanctions created the “legal” framework to seize billions in Venezuela’s foreign assets and specifically targeting the state oil company PDVSA and prohibiting exports to the US market, which previously absorbed over a third of Venezuela’s oil, delivered a catastrophic shock.

The Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) documented that these sanctions caused the Venezuelan state to lose between USD 17 billion and USD 31 billion in potential oil revenue. This loss of hard currency directly reduced the state’s capacity to import food, medicine, and essential goods, increasing mortality rates and creating a real humanitarian crisis. The intensification of US sanctions, particularly those beginning in 2017, contributed to Venezuela experiencing the largest economic contraction in recorded Latin American history, with its Gross Domestic Product shrinking by an estimated 74.3% between 2014 and 2021.

The Iraq playbook, updated: sanctions as economic warfare

The first Trump administration applied a policy of “maximum pressure” to topple Maduro, formalizing the goal of regime change with unparalleled aggression. Apart from the application of punishing oil sanctions, it also led to the farcical backing of Juan Guaidó’s self-declaration as president in January 2019. This also led to the deployment then of US warships and the designation of the Maduro government as a “narco-terrorist” entity, echoing the pretexts for the 2003 invasion of Iraq. This culminated in the subsequent financing of Operation Gideon, an inept maritime invasion by US-backed mercenaries in May 2020 that is now remembered as a “bay of piglets”.

The rhetorical parallels between the two campaigns are striking. In 2003, the Bush administration justified war on the basis of fabricated claims regarding Saddam Hussein’s possession of “weapons of mass destruction” (WMD) and alleged links to terrorism. Similarly, the Trump administration has sought to justify military and covert action in Venezuela by invoking the “narco-terrorism” narrative. Both were attempts to transform a political conflict into a pre-emptive security threat requiring military response.

Yet, the most profound similarity lies in the strategy of economic strangulation used against both nations. From 1990 until the 2003 invasion, comprehensive multilateral sanctions were imposed on Iraq, devastating its civilian population while failing to remove Saddam Hussein. These measures placed severe restrictions on Iraq’s oil exports and strictly controlled the import of goods. The effect was a humanitarian catastrophe, with studies estimating that the sanctions contributed to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of children under the age of five due to malnutrition and a lack of clean water and medicine. Former Assistant Secretary of the United Nations, Denis Halliday, who resigned in protest, called the sanctions “genocidal.” The policy’s brutality was infamously summarized by then-US Ambassador to the UN Madeleine Albright, who, when asked if the deaths of half a million Iraqi children were “worth it,” replied, “We think the price is worth it.”

The sanctions on Venezuela, particularly those imposed in 2019 targeting the oil industry, replicated this collective punishment strategy with even greater initial severity. Unlike Iraq, which eventually received some relief through the UN-administered Oil-for-Food Program (despite US and UK efforts to block vital humanitarian supplies under a “dual-use” rationale), the Venezuelan government was immediately cut off from its primary source of foreign exchange. The Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) argued that the sweeping nature of the 2019 sanctions created a near-total trade embargo that was possibly “more draconian” than the pre-war Iraq sanctions, noting the absence of any comparable humanitarian mechanism to mitigate the loss of billions in oil revenue.

Hegemony and the ideological challenge

The US interest in Venezuela extends beyond just taking control of the world’s largest oil reserves. The primary objective is ideological and political: overthrowing an independent government in Venezuela that has been both a source of support for other progressive governments and a stumbling block for US plans to impose far-right governments in the region. Venezuela’s government represents a node of resistance, and its successful overthrow would reassert the dominance of US foreign policy in the region, sending a clear message to other nations considering charting an independent political and economic course. The threat of intervention is thus not only about economics, but about defending the ideological integrity of the Monroe Doctrine in the 21st century.

The latest round of escalation of hostility toward Venezuela under Trump represents an acute and dangerous phase, marked by recent extrajudicial strikes in the Caribbean and explicit threats of land strikes. So far, at least 32 people have been killed in at least seven such attacks since early September. Some of the victims have been confirmed as citizens of Colombia and Trinidad and Tobago. The administration has accused the victims of being “narcoterrorists” without providing concrete proof, with their families asserting those killed were fishermen.

The campaign against Venezuela is fundamentally a continuation of a two-century effort to maintain imperial control over the region. Trump’s mad, relentless drive to topple Nicolás Maduro as part of a historical compulsion to assert dominance, not only through sanctions and support for internal unrest, but now through extrajudicial killings at sea and threats of land operations, has brought the region to the brink of a massive conflict. Such a war would not only be a disaster requiring a vast deployment of troops, but would almost certainly destabilize all of Latin America and spill far beyond Venezuela’s borders. However, a majority of the American people have shown they oppose using military force to invade Venezuela and a bipartisan resolution was raised by California Senator Adam Schiff and Kentucky Senator Rand Paul to block Trump from using force against Venezuela. Yet, the ultimate check on this dangerous adventure may yet rest with the American public, who must demand transparency and an immediate end to the march toward another disastrous war.

Manolo De Los Santos is Executive Director of The People’s Forum and a researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. His writing appears regularly in Monthly Review, Peoples Dispatch, CounterPunch, La Jornada, and other progressive media. He coedited, most recently, Viviremos: Venezuela vs. Hybrid War (LeftWord, 2020), Comrade of the Revolution: Selected Speeches of Fidel Castro (LeftWord, 2021), and Our Own Path to Socialism: Selected Speeches of Hugo Chávez (LeftWord, 2023).

Courtesy: Peoples Dispatch

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.